Earlier this year I was at a conference and heard from other attendees that the Intel booth was giving away IoT gateways. Never one to turn down free conference swag, I hurried over to the Intel booth and was told to pick up a gateway out of a pallet of boxes just delivered (and rapidly disappearing).

The Intel IoT gateway series is codenamed Moon Island, but the design targeting the transportation market is codenamed Clanton Hill. Clanton Hill known to us mortals as the “Intel DK200 Series Gateway Solution for the Internet of Things (IoT)” quite the mouthful.

Let’s get down to it.

Availability

Unless you happen to be at a conference where Intel reps are handing these out like candy, I don’t think it’s practical to try and buy one yourself:

Some interesting details to note about this product:

- Although released in 2014, the DK200 still costs more than the new MacBook (3,712.50 EUR versus 3,199 EUR)

- It’s End Of Life

When a low volume product goes EOL and you still have stock, I guess giving it away at conferences is the next logical step.

Hardware Specifications

The DK200 (datasheet) is targeted toward the transportation industry, and it really shows in the appearance of the device:

Only available in ‘Cosmic Black’

I don’t work in the transportation industry, and have never seen connectors that look like this before. They’re very well made, and I suspect probably do a good job of keeping dust, dirt, and debris out of the ports. Since I don’t wish to make a mess by throwing dirt and debris at it, I’m going to have to trust the engineers who designed it.

The build quality is quite good, as one might expect from a device selling for 3,700 EUR. Nearly every screw is secured with loctite to prevent vibration from loosening them:

No pentalobe nonsense here

However, I was surprised to find that despite all the physical hardening applied to the enclosure, I couldn’t find any information on an IP rating. In fact the top and bottom of the case don’t appear to offer any additional dust or water seal. There’s clearly been a lot of thought put into the design of this enclosure to withstand vibration and dirt, so it’s strange that there doesn’t seem to be water protection of any kind.

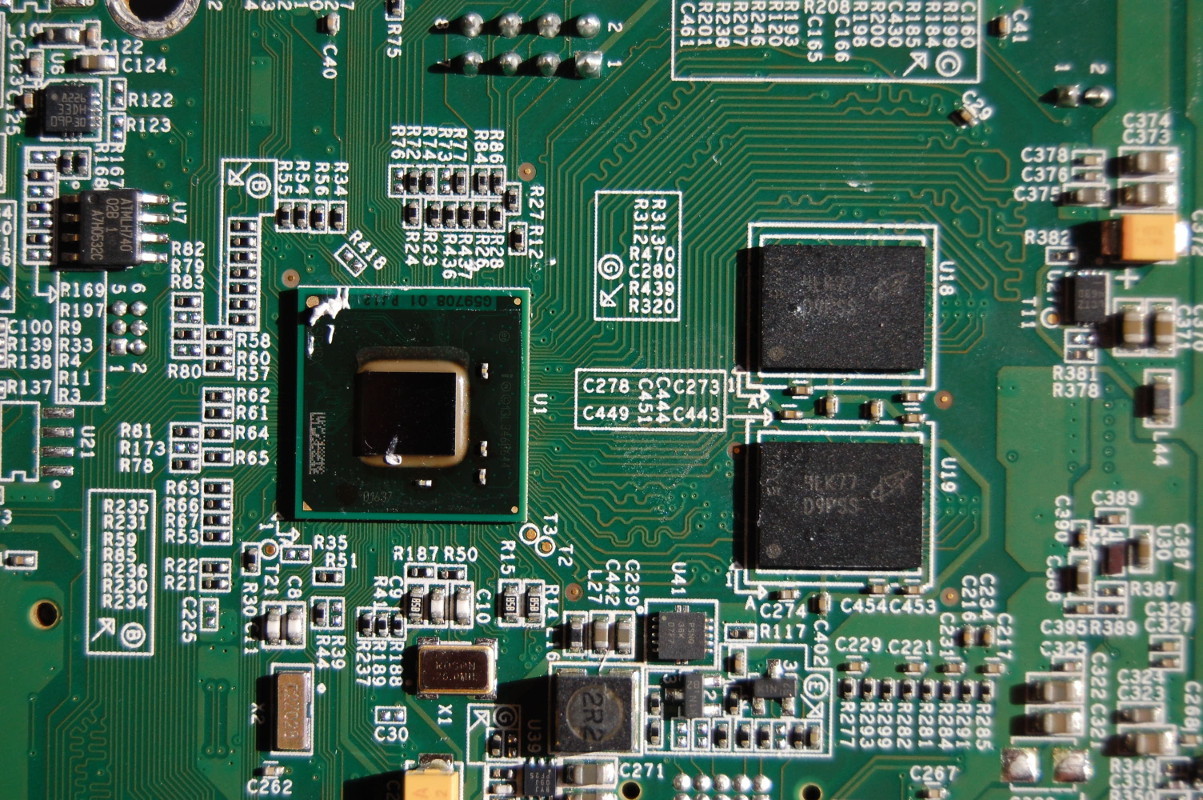

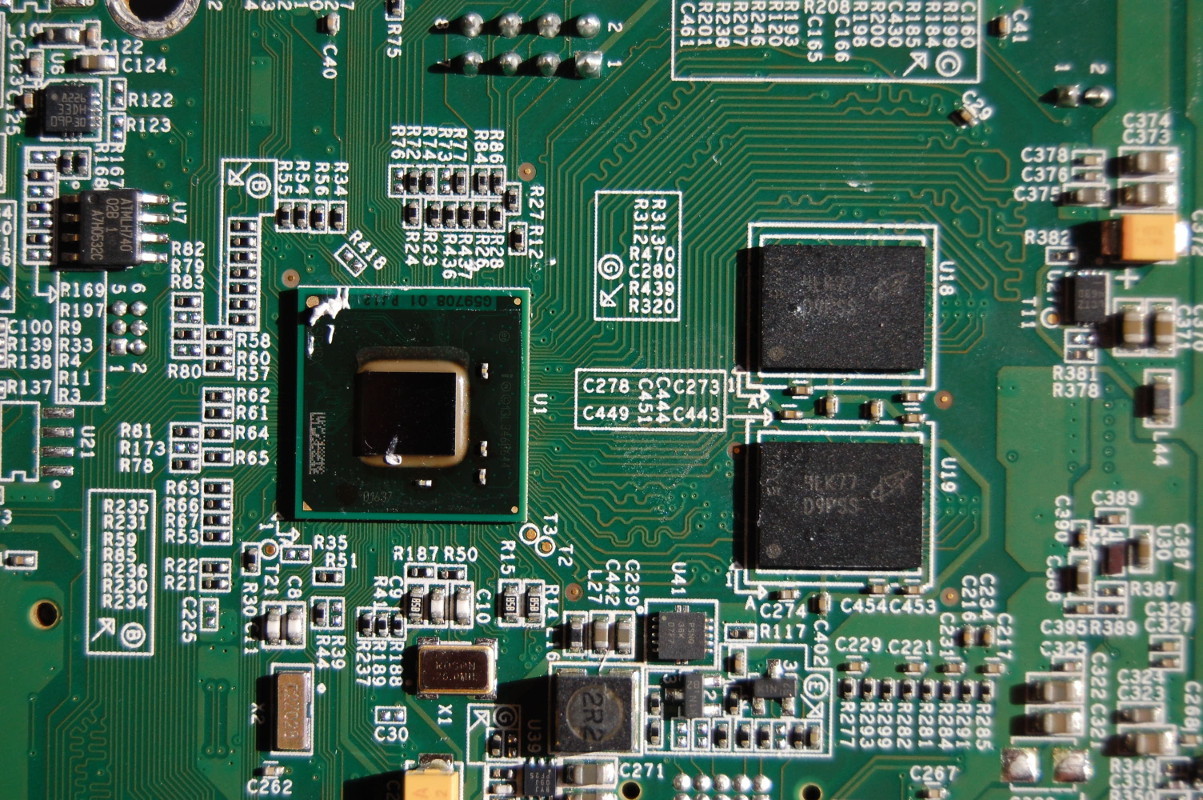

Processor

The Intel Quark series SoC was introduced in late 2013. The X1020D in the DK200 is a single core SoC based around a 80486 core running at 400MHz, with modern I/O and memory.

In 2014 a leaked product roadmap suggested a successor to the X1000 series named “Dublin Bay” to be released in 2015. Then news emerged that “Dublin Bay” had been cancelled, to be replaced by “Liffy Island” and “Seal Beach” which would be released in 2015. As of late 2016 Intel has not released a direct successor to the X1000 series, and there is no new news of “Liffy Island” or “Seal Beach” being cancelled (or released). So it’s anyone’s guess whether Intel is still even interested in the IoT gateway market.

Storage

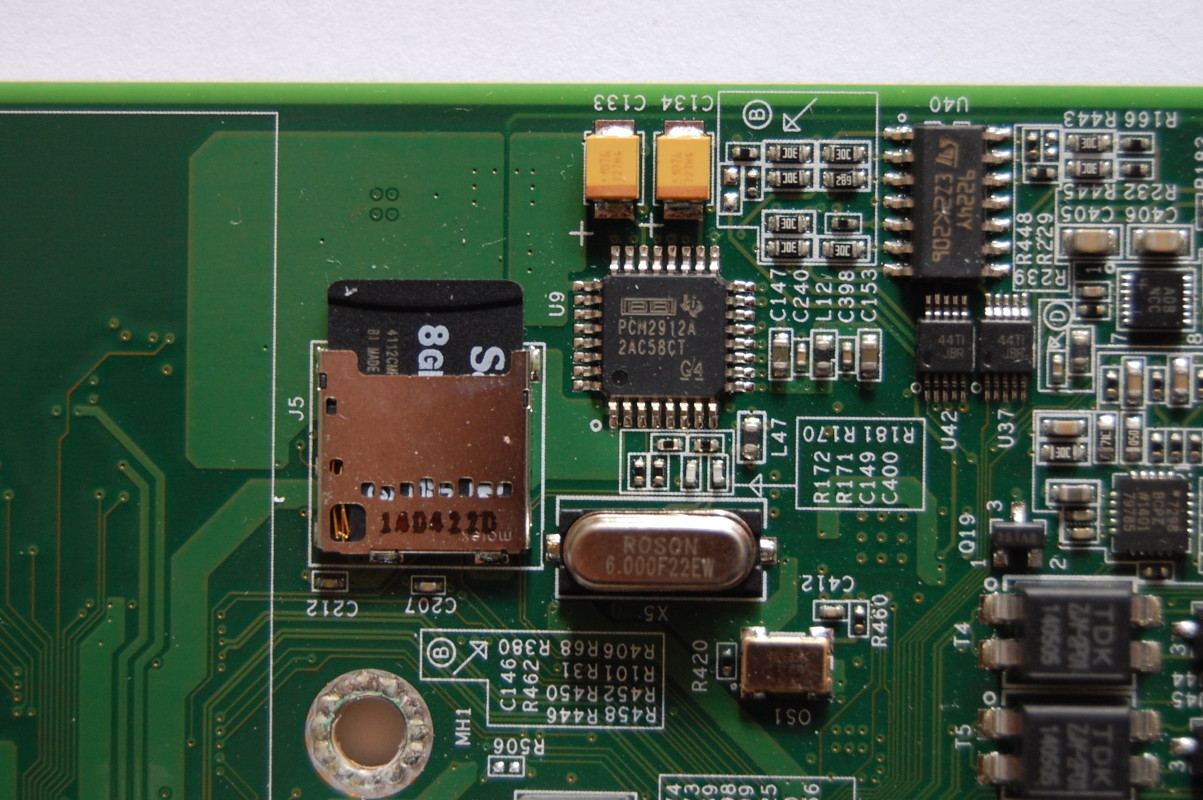

The DK200 doesn’t include any of the typical storage buses like SATA, NVMe, or NAND (EMMC). This is not overly surprising given the embedded nature of the hardware (requiring lower power) and the simplicity of the Quark processor.

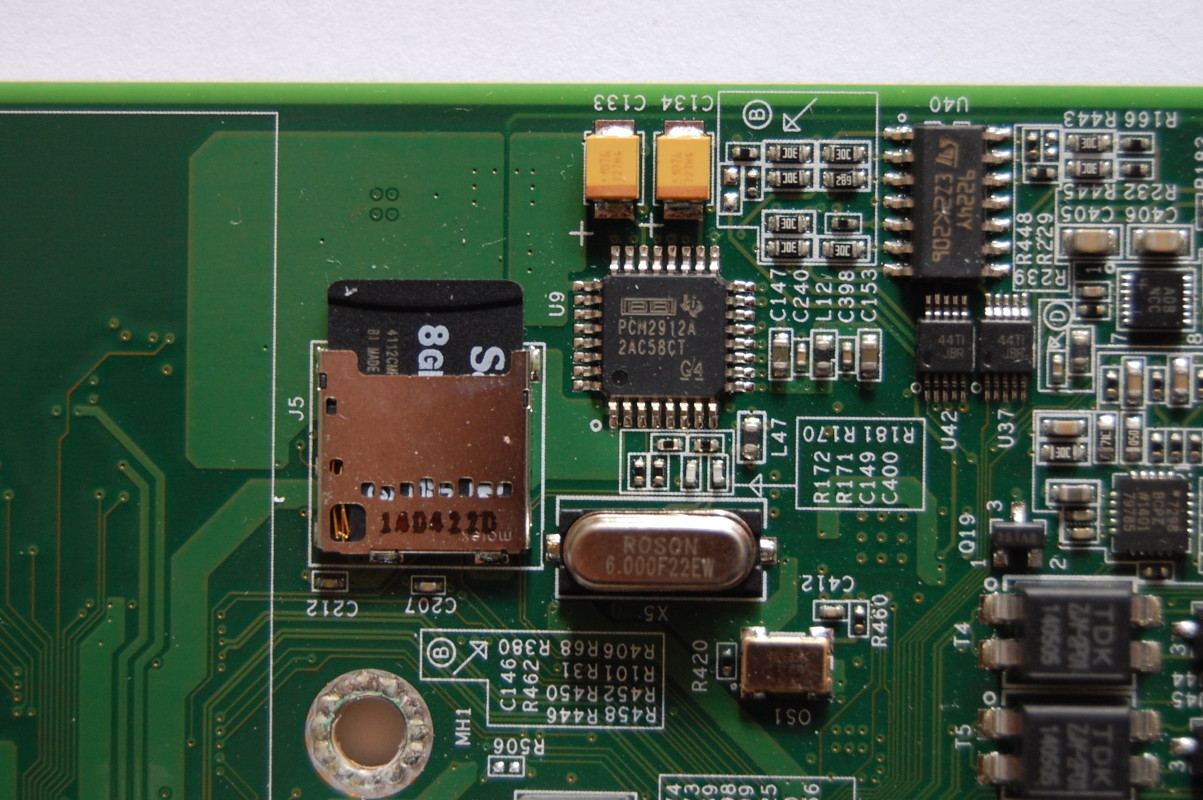

The only storage option is a micro SDHC card, and the DK200 includes an 8GB class 4 micro SD card:

Given that it’s a class 4 card, the performance is quite poor. Use of an SD card for storage isn’t a bad decision per se, but the DK200 uses ext3 for the root partition. Ext3 is not a flash aware filesystem. SD cards have only basic wear leveling, and ext3 has no wear leveling. So it hardly seems like the appropriate combination of storage and filesystem for a headless embedded device with an expected lifetime of 5-10 years.

Input and output

- Dual 100Mbit Ethernet controllers

- 3 x USB 2.0 host and 1x device

- Audio in/out

- CAN bus

- RS-232

- GPIO

- 1x half-height mini PCI-e slot (populated with Intel 7260)

- 1x full-height mini PCI-e slot (unpopulated; for 3G modem/GPS)

The Intel documentation also mentions ZigBee, however this is an external device, presumably attached via the USB bus.

Power consumption

Development platforms aren’t known for being highly optimised devices. They often include extra I/O which would not necesssarily be included in the final product, and as such do not have the same energy efficiency as a finished product.

This being said, I was quite surprised that a device intended for 24/7 operation in an embedded environment, and especially serving the “Internet of Things” market, could be so energy inefficient. Issuing a poweroff command in Linux results in the platform going into an S5 (shutdown) state. I was surprised to discover that the energy consumption in the S5 state is 2W. This seems quite high for a device which includes an ignition input for automatic power-on and shutdown.

When booting, the device peaks at 7.9W consumption, while the idle power consumption is 7.5W. This is almost certainly due to the added peripherals as the TDP of the Quark processor is only 2W.

It’s difficult to see how Intel expects the Quark platform to compete with ARM. My PandaBoard ES, an ARM-based development board from 2011, peaks at 4W, idles at 2W, and draws nothing when off. Now some might argue that comparing an ARM board from 2011 with an Intel IoT gateway from 2014 isn’t valid, but they do have a lot of similar features. Now, I will grant that the PandaBoard is not in a rugged enclosure with fancy connectors, but since it cost 95% less than the DK200 does, there’s some room in the budget for an enclosure and funky connectors. And, since Texas Instruments has stopped making OMAP chips, the PandaBoard gets about the same amount of vendor support as the DK200!

Software

I will be exploring the software of the DK200 in a follow up post. Stay tuned!