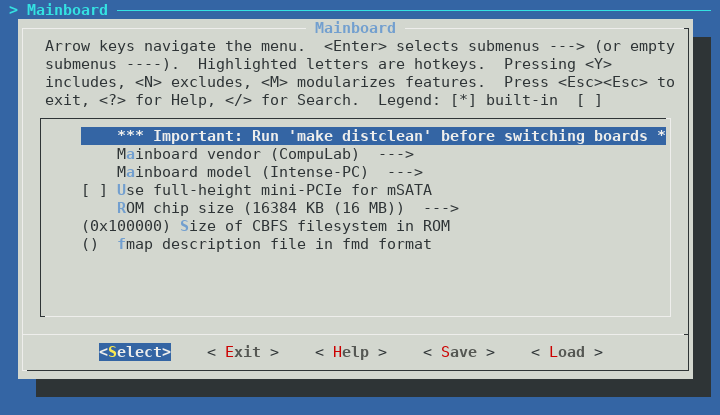

Introduction

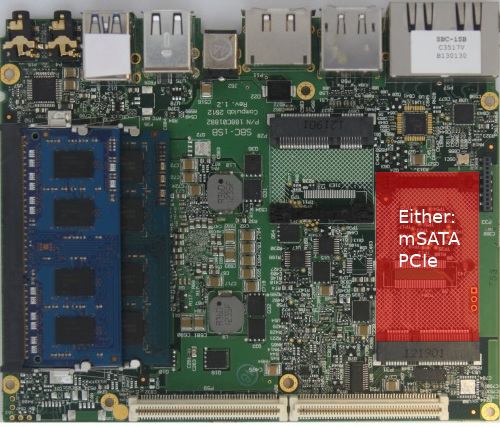

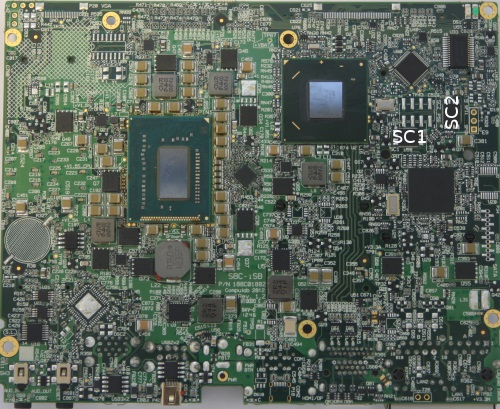

The CompuLab fitlet2 is a new model in their fitlet series. The new fitlet2 switches from AMD to Intel’s Apollo Lake SoCs. My unit has the Intel Atom x7-E3950.

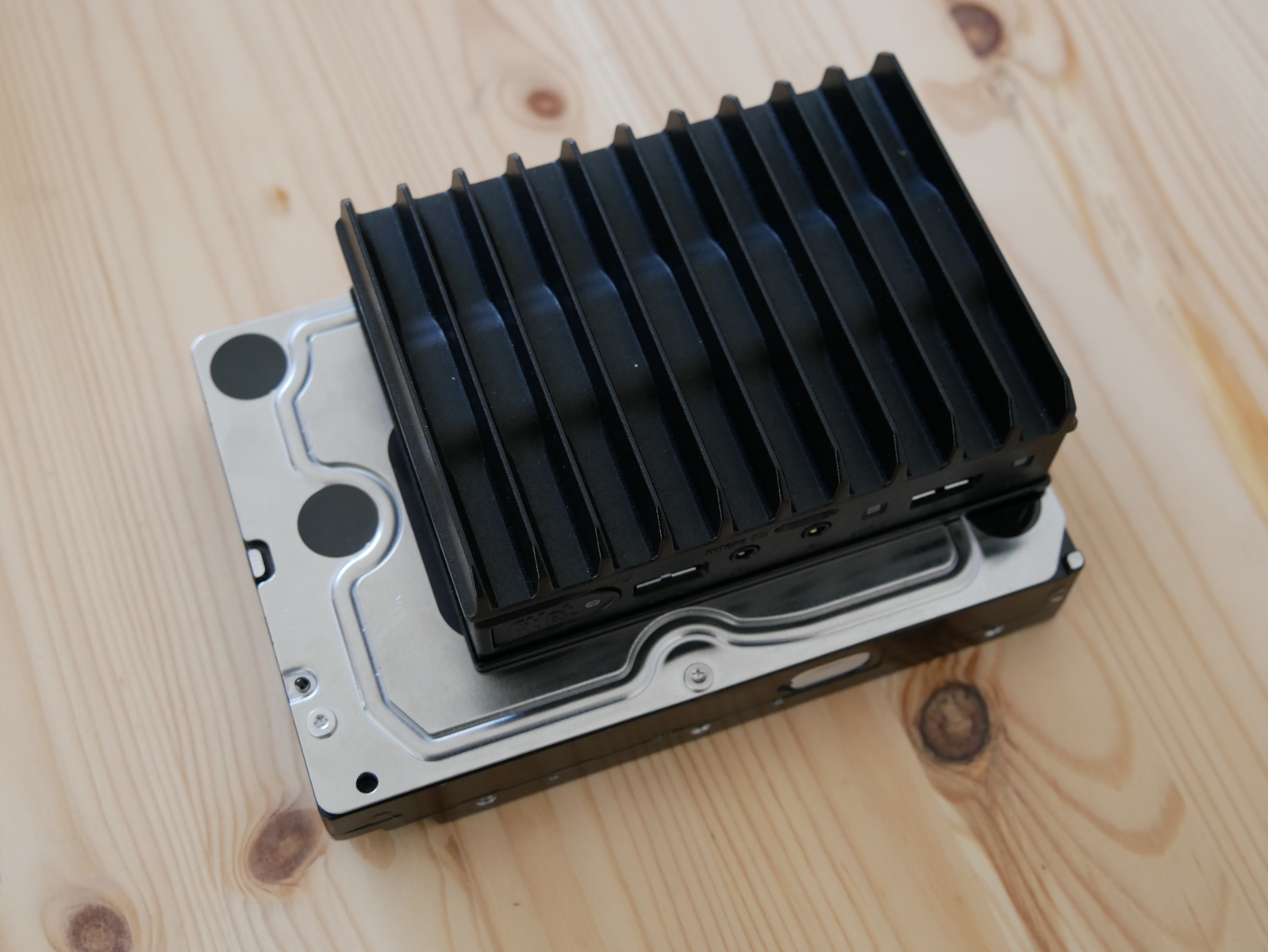

First we should discuss the elephant in the room, the fitlet2 is quite small. Here is the fitlet2 compared to a standard 3.5″ hard drive:

Disclaimer: My unit was provided by CompuLab to evaluate its potential as a target for coreboot, and to poke at their firmware (?). I received no compensation for this review, apart from the gratis hardware, and CompuLab did not have any input or influence on the review except to clarify my questions.

In the box

The fitlet2 is quite minimal, in the box you have:

- fitlet2

- 12V 3A power supply with plugs for AU/EU/UK/US

- Small sheet of information (FCC certification, manual download, etc)

There are no other cables or accessories included in the box.

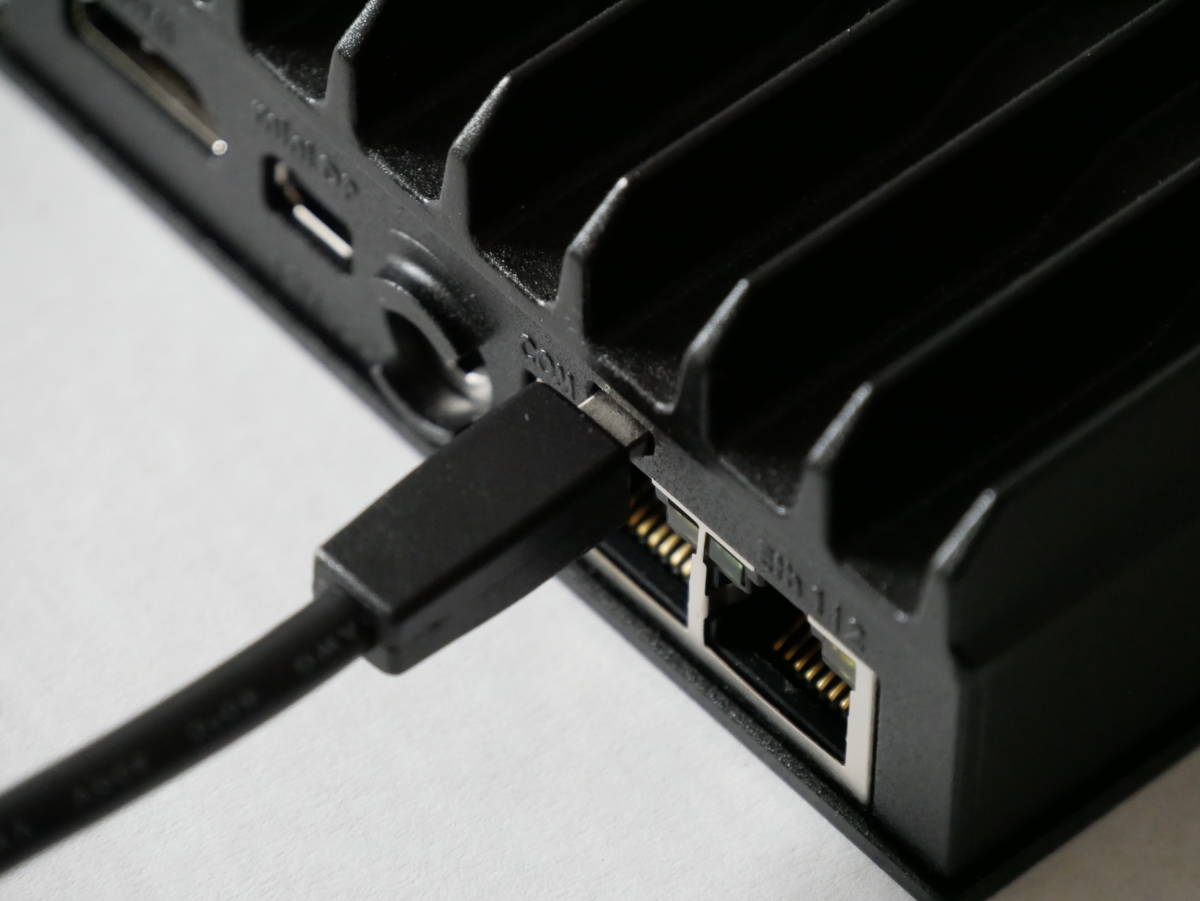

CompuLab use a small form factor port for RS-232, so if you plan to use the onboard RS-232 port, you will need to remember to order the accessory cables package during checkout.

I found the lack of rubber feet a bit strange. The bottom case is slightly elevated thanks to some protruding metal at each corner, but without the rubber feet the device is very slippery on most surfaces. It would be nice if CompuLab included rubber feet in the box that you could apply if you wanted to put the device on your desk.

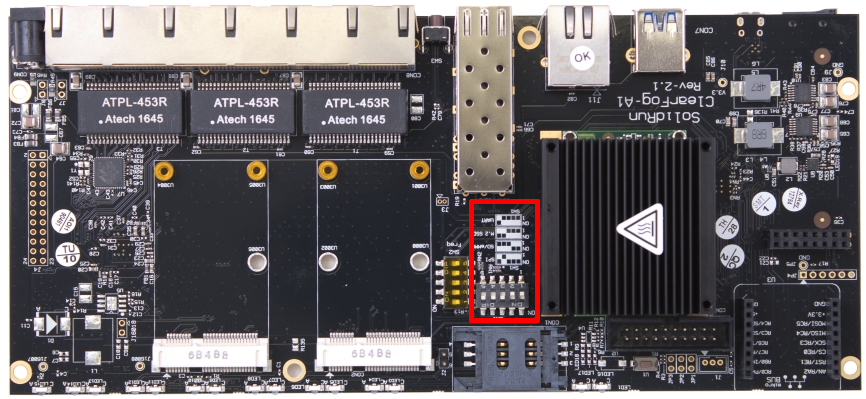

Hardware

- Intel Apollo Lake SoC: Atom x5-E3930, Celeron J3455, or Atom x7-E3950

- Up to 16GB DDR3L-1866 Non-ECC (single SODIMM)

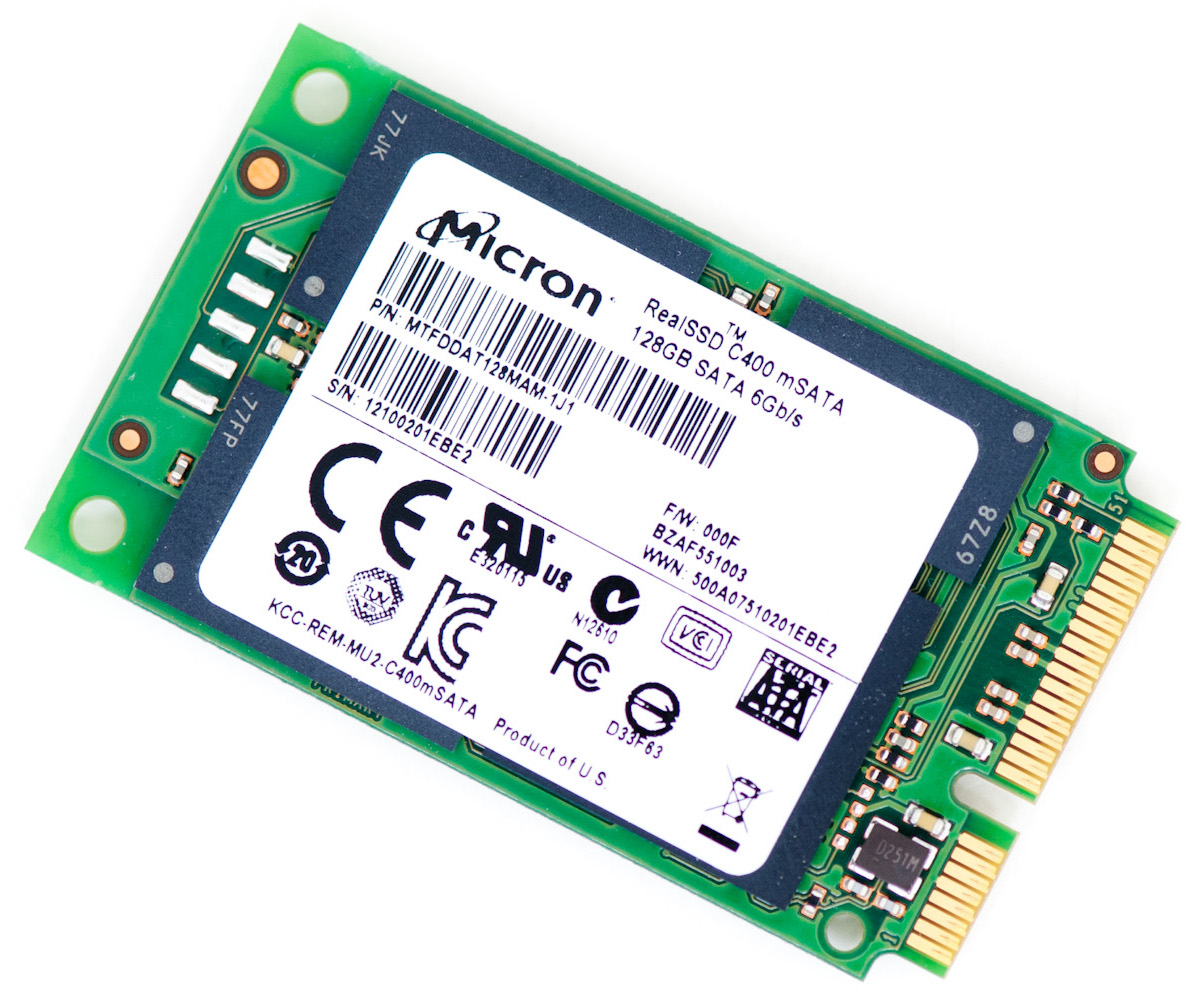

- M.2 SATA storage

- M.2 NGFF for WiFi or cellular modem

- Dual Intel Gigabit Ethernet interfaces (Intel i211)

- HDMI 1.4b and mini DisplayPort 1.2 outputs supporting 4K resolution

- Two USB 2.0 and two USB 3.0 ports

- MicroSD card reader

- 3.5mm Audio in/out

The CPU in the fitlet2 is low-end. I personally don’t feel there’s any point in trying to talk up the capabilities of the Intel Atom series because they weren’t designed for performance. The Atom specializes as a low power CPU, with the Atom x5-E3930 consuming 6.5W, the Celeron J3455 consuming 10W, and the Atom x7-E3950 consuming up to 12W.

However, there are other areas where the fitlet2 surprises, such as the ability to accept a 16GB SODIMM. The Atom x5-E3930 and x7-E3950 also support ECC memory, although CompuLab confirmed that to offer the Celeron J3455 version they’ve removed ECC support from the motherboard. Be sure to check the fitlet2 RAM Qualified Vendor List (QVL) before purchasing.

Somewhat disappointingly, 4K@60Hz is not supported on both display outputs. This is an Intel Apollo Lake limitation, and will hopefully be resolved in their next generation SKUs. If you want to use 4K@60Hz via HDMI, you’ll need to buy an active adapter to convert the mini DisplayPort output to HDMI 2.0. DisplayPort MST is supported, so you can daisy chain DisplayPort MST capable displays. Unfortunately in my testing I was not able to daisy chain any combination of 4K displays. Daisy chaining two 1080p displays functioned normally. HDMI also functions while DisplayPort MST is active, so in my testing I was able to have three simultaneous 1080p displays driven by the fitlet2. I only have two 4K capable displays, so I’m not able to test all possible display combinations.

The micro SD reader is a nice inclusion, however the slot is so recessed in the front panel I found it impossible to insert or eject a micro SD card with my fingers. I ended up using another SD card to gently push the micro SD into the slot. Even with this helper, I found it difficult to insert and remove the micro SD card. This experience convinced me that if you’re going to use a micro SD card frequently with the fitlet2, an external reader is a must. If your plan is to use the micro SD as expandable storage that is rarely removed, then I don’t think that would be an issue.

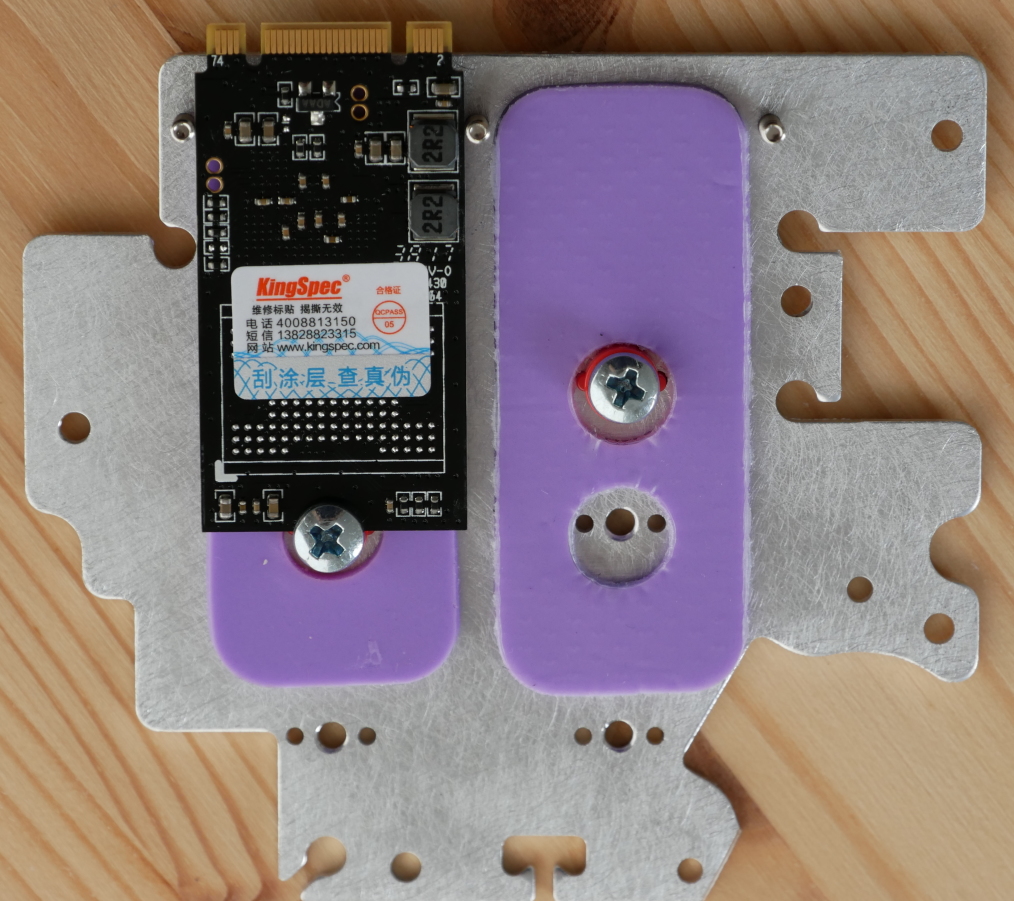

My unit came with 4GB of RAM and a 64GB M.2 SATA SSD installed. The M.2 SSD (2242) in my unit is the Kingspec NT-64.

I have been using Kingspec SSDs in low performance applications (such as firewalls) since the beginning of 2017 and haven’t experienced any failures or issues, so while they’re relatively unknown in the West I don’t think they’re necessarily a bad choice. If you want to add a name brand M.2 SSD such as Transcend or ADATA you would probably be better off to buy the barebones model and add the SSD yourself.

The stock model only accepts 7-20V DC input. CompuLab does offer a build-to-order (BTO) version of the fitlet2 which accepts 9-36V DC input.

Software

CompuLab isn’t currently shipping the fitlet2 with any OS. But since the fit-iot website shows a render of the case in the Linux Mint colour scheme, it’s possible they will introduce a bundle with Linux Mint in the future as they have done with past products like the MintBox 2.

I do plan to test Linux, BSD, and Windows 10 IoT on the fitlet2. However I decided to wait on performing any extensive testing or benchmarks until patches for Meltdown and Spectre are available for all the above operating systems. Thoroughly evaluating an OS takes some time, so it may take me some months to get around to reviewing the fitlet2 with the above operating systems (and I have other projects in my pipeline too).

I’m also waiting to hear back from CompuLab on whether they plan to include support for Secure Boot. While some people are against Secure Boot, I think including the option to enable it and letting the user define their own keys would be a wise idea. For hardware intended to be installed in an industrial scenario and left unattended for years in the field, cryptographic verification of the entire boot process is vital to maintaining endpoint security.

Xubuntu 17.10 installs and runs nicely on the fitlet2. Average power consumption at the desktop is around 4.5W. There does appear to be a minor issue with Xubuntu not fully powering off the fitlet2, which CompuLab is aware of and will hopefully be resolved soon.

Conclusion

The fitlet2 is not the smallest x86 platform available (that honour would probably go to the Intel Compute Stick), but certainly offers a lot of I/O and expansion options for its diminutive size.

The fitlet2 is similar, though slightly less I/O rich, to the PC Engines APU2 (Quad Core, 2/4GB RAM, 3x GigE, 3x mPCIe, SD reader) while offering more convenient interfaces like HDMI and DisplayPort for people who don’t live in a 115200 baud world.

The dual Gigabit Ethernet interfaces would make it ideal as a low power firewall or an IoT gateway. Triple display support (DisplayPort MST & HDMI) out of the box could also see the fitlet2 used to power an informational or advertising display. Given CompuLab’s “IoT” marketing for the fitlet2, maybe there will even be a LoRaWAN FACET module available at some point in the future?

For consumers interested in an inexpensive, low power, and fanless PC, the fitlet2 is also functional as a desktop or a small server. It supports multiple displays and has USB3.0, but don’t expect miracles from the CPU or GPU. Worth noting is the stock model doesn’t support WiFi, though there are many inexpensive USB to WiFi adapters which are compatible with Linux and Windows, should you wish to add WiFi later. The fitlet2 also lacks USB Type-C which is supported by Apollo Lake and is slowly becoming more mainstream.

The fitlet2 comes with CompuLab’s standard 5 year return to depot warranty, but CompuLab also offers the Atom x5/x7 models with an extended 15 year availability. This is an important consideration for business customers who want stability in their supply chain or plan to develop and support long-lived products with the fitlet2 (e.g. CNC controllers, PLC applications, IoT gateway).

With barebone models starting from $154 I think the fitlet2 offers good value for the price. I feel CompuLab have a good offering here for the industrial segment as the fitlet2 is much more affordable than previous CompuLab products like the Intense PC, and competing products from companies like Logic Supply.